First Consensus Meeting on Menopause in the East Asian Region

Country-specific information on the menopause in Japan

Hideo Honjo, Mamoru Urabe, Tomoharu Okubo, Noriko Kikuchi

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan

The Japanese population [1]

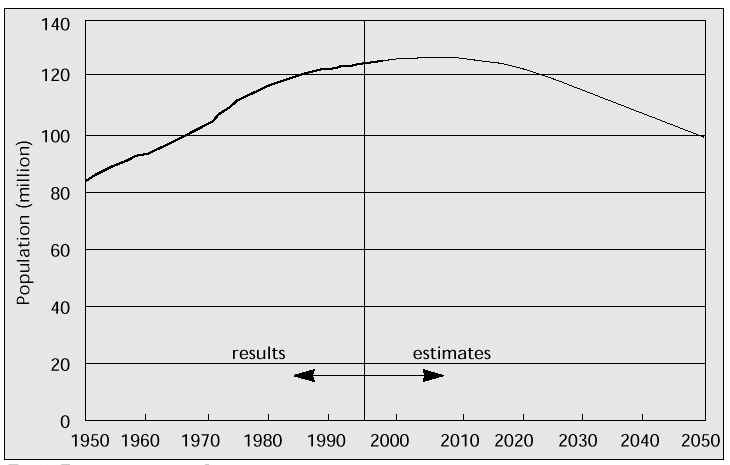

Japan counted more than 125.5 million inhabitants in 1995; the population is increasing slightly now. It counted 83.2 million people in 1950 and 111.9 million in 1975. The population is estimated to grow until the year 2007, reaching a peak of 127.7 million, and to decrease thereafter (Fig. 1). The dynamic statistical tendency of the Japanese population is thought to be following that of Europe or North America.

The population increase is due to an improvement in environmental hygienics, advances in the standard of living, and to the development of medical care services. In fact, the hygienic improvements and the advances in the standard of living have made Japanese people more healthy and have caused a reduction in the incidence of many infectious diseases and the ensuing mortality. As in other countries, the development of medical care services was followed by a reduction in neonatal mortality. The expected decline of the population after 2007 is related to a decrease in fertility rate, since ever more women are starting a working career and are getting married late. Total fertility rate was 1.50 in 1994, implying a decreasing ratio of children vs. working population.

Fig. 1: Total population in Japan.

Life expectancy of Japanese people [2]

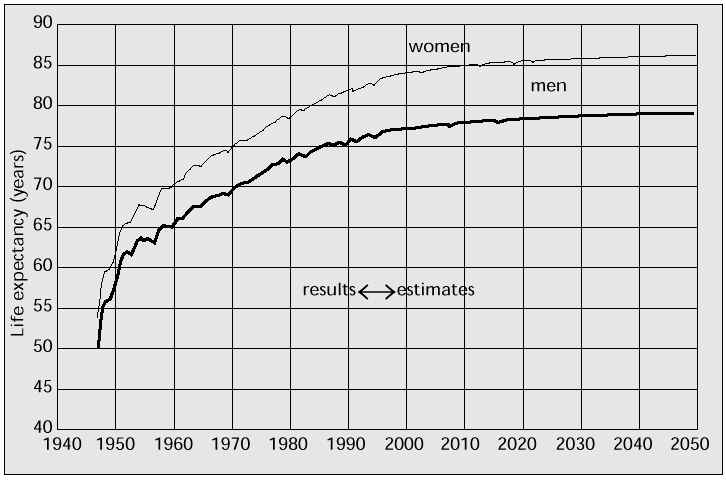

The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research in Japan has calculated the average life expectancy from 1950 until the year 2050. The average life expectancy in women increased from 63.0 years in 1950 to 82.84 years in 1995. It has increased by 2.4 years only during the last decade, but it will continue to increase in the future and is estimated to reach 84.12 years in 2000 and 86.47 years in 2050 (Fig. 2). The life expectancy gap between women and men is reported to be 6.48 years; it will broaden to 7.04 years in 2050. Japan has become a country where many people live to an advanced age.

Fig. 2: Change of Japanese life expectancy.

On a global scale, the Japanese people are thought to have the longest life expectancy. For example, in the United States, one of the most advanced countries in the world, life expectancy in 1992 was 79.1 years in women and 72.3 years in men; in Switzerland, which is thought to have the highest standard of living, of environmental hygienics and of medical care services, 1990-1991 life expectancy was 80.9 years in women and 74.1 years in men; in Sweden (1994), the European country with the longest life expectancy, it was 81.38 years in women and 76.08 years in men; and in Australia, an advanced country representing Oceania, life expectancy in 1992 was 80.41 years in women and 74.47 years in men.

On average, life expectancy in Asia is rather lower than in other regions, such as North America, Europe and Oceania. For example, life expectancy in India from 1981-1985 was 55.67 years in women and 55.40 years in men. If, however, we restrict our focus to Far East Asia, life expectancy approaches that of North America and Europe: in Hong Kong (1994), it was 81.16 and 75.84 years in women and men, respectively; in China (1990-1995), 70.45 and 66.70; and in the Republic of Korea (1991) 75.67 and 67.66 years, respectively. Nowadays, Japan has the longest life expectancy in Far East Asia and in the world. However, it is not beyond the bounds of possibility that other countries could approach or even surpass Japan in the near future. It remains a challenge to researchers in Japan as well as in other countries to find out about the reasons for the high life expectancy in Japan.

Causes of mortality in Japanese women

It is our impression that more elderly Japanese die from cerebral infarction or haemorrhage compared with people in Western countries. It is also our impression that many Japanese, especially women, die of old age. The top three causes of death are malignant neoplasia, cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and coronary heart disease (CHD). Male and female CVD mortality rates from birth have decreased remarkably (in women, from 27.0% in 1965 to 19.66% in 1995). The female mortality rate from malignant neoplasia, on the other hand, has been increasing from 12.4% in 1965 to 18.76% in 1995. The mortality rate from CHD has fluctuated during the last few decades. Mortality from the above-mentioned top three causes of death is responsible for more than 50% of the total mortality. As alluded to in the previous section, the higher the life expectancy, the higher the mortality rate from the top three causes of death is to be anticipated. Two of these, CVD and CHD, are closely connected to the menopause.

CHD mortality rate in Japan is much lower compared with Western countries: it is 128.6 per 100.000 in Japan, compared with 276.4 in the United States, 180.9 in France, and 328.3 in Great Britain. The female CVD mortality rate is 100.7 in Japan, compared with 67.2 in the United States, 92.8 in France, and 159.8 in Great Britain. Since much of the lifestyle in Japan has been westernized, such as dietary habits and the like, it would be quite unrealistic to expect a decrease in CHD mortality rate. As for the most probable causes of death in Japanese women born in 1995, the number-one cause is CVD (19.66%), in second place we see malignant neoplasia (18.76%), and the third-most cause is CHD (17.63%). In males, the top position is taken by malignant neoplasia (28.36%), the second place by CVD (15.29%), and in third place we find CHD (14.61%).

Of course, part of our grappling with vascular diseases is preventing them, which is why it is important to pay attention to menopause-related aetiology of these diseases in women.

Proportion of elderly people in Japan

As in other advanced countries, the Japanese are facing the problem of an increase in the proportion of elderly people. According to the latest (1995) data, classifying the total population into three age groups, the composition of the Japanese population was as follows: 0-14 years, 20.03 million; 15-64 years, 87.26 million; 65 years and over, 18.31 million people. It is estimated that the latter group of elderly people will count 33.12 million in 2025 and 32.45 million in 2050.

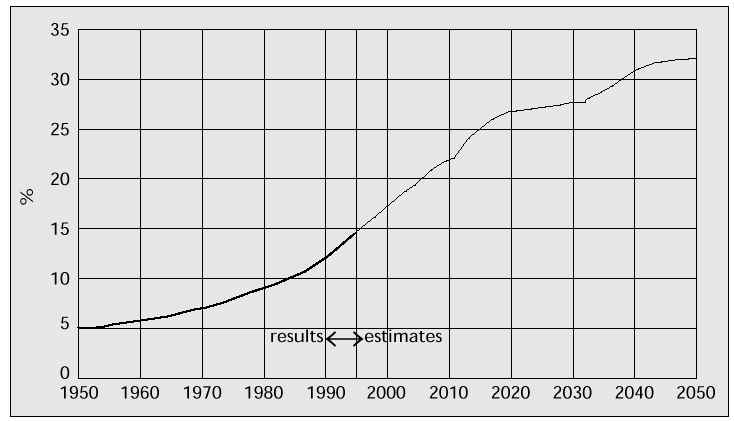

The percentage of the elderly population was 14.6 in 1995, increasing to 25.2 in 2015, 28.0 in 2030, peaking in 2049 and stabilising at 32.3 in 2050 (Fig. 3). There is, therefore, an urgent need for finding the key to settlement of this problem.

Fig. 3: Percentage of elderly people.

Compared with advanced Western countries, the elderly Japanese population is increasing at a more rapid rate. For instance, in 1985 the percentage of elderly people in Japan was 10.3 vs. 11.9 in the United States. In the near future, however, Japan is estimated to surpass the United States in this respect. In 2025, the percentage of elderly people in Japan will reach 25.8 (which is 2.25-fold of that in 1985) compared with 18.5 in the United States (1.55-fold of that in 1985). It is self-evident and of utmost importance that Japan faces the most serious ageing-society problem in the world.

The issue for Japanese society

As mentioned above, the Japanese people are being confronted with the issue of a severely ageing society in the near future. The problem is multicausal, but can easily be separated into its constituents: the female expansion in societal participation and labour force, marrying late in life and having less children. Japanese parents want their children to enjoy a good education until college, which is an expensive undertaking. Due to the prevailing depression and the cramped Japanese housing conditions, parents cannot have more children.

The average age of menopause in Japan is 50.0±0.1 years [3]. The problems described do, of course, relate very much indeed to Japanese obstetricians/gynaecologists. We have to educate women of reproductive age and try to find a solution for the treatment of infertility. We can also improve the quality of life in climacteric and elderly women.

The Japanese Menopause Society has been established in 1986. The society supports the progress of studies concerning physiological, pathological and clinical problems in peri- and postmenopausal women. By means of such activities, the society hopes to make a significant contribution to human and social welfare. Membership nowadays exceeds 1500, comprising members from a variety of occupational and specialist categories, enabling multiform discussions and a varied and holistic approach. The Journal of the Japan Menopause Society has been published periodically since 1993.

In a social system such as in Japan, it is an essential requirement for retired people, single persons living on a retirement allowance, diseased, bedridden elderly and demented people, etcetera, etcetera, to feel that they can equally live a useful life. With old age approaching, the number of elderly people in need of nursing care is increasing. There is also an increase in the number of elderly people living on their own in big cities. Every Japanese is part of the national health care insurance system; this system, however, is going through a financial crisis because of the escalation of medical expenses due to the aging population. Public nursing insurance, a law of nursing support and nursing homes for the elderly are now being developed in Japan. It will, however, take a long time for all these to become realised.

Nursing homes are becoming increasingly important and they are badly needed. In former days, Japanese families were larger, and different generations of one and the same family were living together. Nowadays, like in other developed countries, the nucleus of family life is coming apart. As a consequence, many elderly people in Japan live a solitary life, especially in the big cities. Their number now reaches 2.1 million, which is 12.1% of the total elderly population. Many of them are in need of nursing, daily supply of meals, and social contacts within their living area. Some of them want to live in an old peoples’ home. In 1996, there were 1571 of these homes with a housing capacity of 137,333, not enough to cope with the demand.

Dietary habits and phytoestrogens

Recent publications have highlighted the differences between countries in the incidence of many diseases, including coronary heart disease, breast cancer, endometrial and ovarian cancer, and climacteric symptoms. The differences have been attributed to different diets and lifestyles, among others. As far as dietary habits are concerned, natural oestrogenic substances present in plants may play a role in these differences. Phytoestrogens, found in many plants, are defined as plant substances structurally or functionally similar to estradiol (E2). Isoflavones and lignans belong to this group.

The two primary oestrogenic isoflavones in soybeans are genistein and daidzein and their conjugates [4]. These phytoestrogens bind to oestrogen receptors. Their relative oestrogenic potency, as determined by in vitro bioassays based on the oestrogen-specific enhancement of alkaline phosphatase activity in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells of the Ishikawa-VAR I line, is 0.084 for genistein and 0.013 for daidzein, compared with estradiol (=100) [5]. The effects of genistein appear to be tissue-specific, with oestrogen-agonistic effects on plasma lipid metabolism and preservation of bone mass similar to oestrogens, but without oestrogenic effects on the uterus at these same doses [6].

Many soy products (such as tofu, miso, age, among others) are part of the Japanese diet. These soy products and vegetables include phytoestrogens, especially daidzein. Climacteric symptoms in Japanese women are always said to be weaker than in European women. Phytoestrogens in the Japanese diet may be one of the reasons for this phenomenon. Mary et al. [7] reported that the beneficial effects of the unextracted soy protein isolate containing phytoestrogens on lipids and lipoproteins might suggest protection against the development of coronary artery atherosclerosis. Indeed, in Japan, coronary heart disease is less frequent than in European countries; however, the oestrogenic effects coming with the foodstuffs may not be the only explanation, for the same food contains less cholesterol than animal products.

Japan counts approximately 4-5 million osteoporotic patients today, almost the same as in European countries. The incidence of osteoporosis in females is more than three times that in males, due to a considerable increase of the disease in postmenopausal women. Similar to coronary heart disease, osteoporosis in females is associated with postmenopausal oestrogen deficiency.

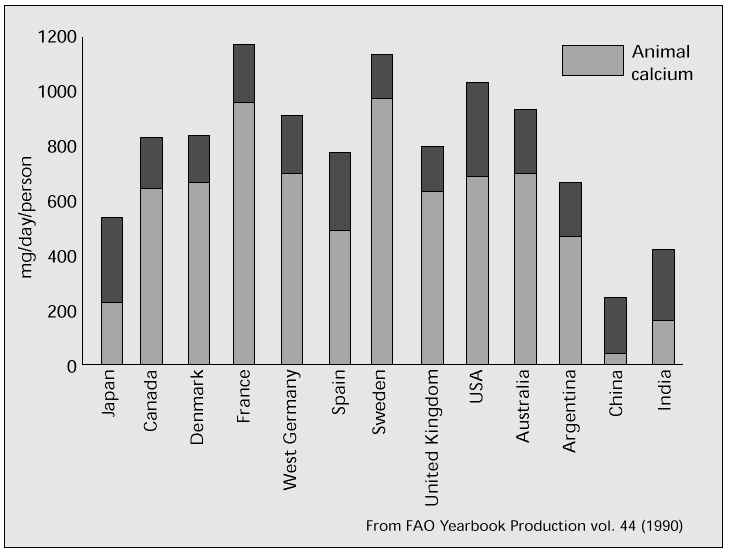

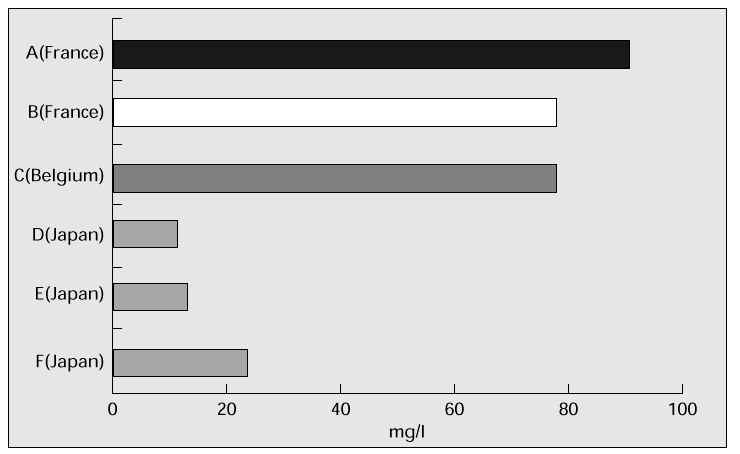

Another specific result of dietary habits in Japan is a deficient calcium intake. It is well known that bone mineral density is strongly influenced by calcium intake. 600 mg of calcium is the necessary and recommended daily dose for Japanese. It is, however, very difficult to obtain enough calcium from the normal daily meal in Japan. Figure 4 shows the average daily calcium intake in various countries. In comparison with European countries, there is a tendency towards less calcium intake in Asian countries. In many European countries, daily calcium intake is ±1000 mg, significantly higher than in Asian countries. Daily calcium intake in Japan is only 550 mg, and especially intake of animal calcium is very low compared with European countries. This difference may be due to the typical Japanese dietary habits. The main dietary sources of calcium in Japan are vegetables and fish. About 50% of calcium is coming from vegetable sources, such as grains, green leafy vegetables, beans ans seeds. It is well known that the best dietary sources of calcium are milk and milk products, such as yogurt and cheese, but the Japanese habitually have a low milk consumption. Whereas in the United States milk and milk products contribute about 76% of daily calcium supply, in Japan it is only 26%.

Fig. 4: Calcium intake: average in 1987, 1988 and 1989. From FAO Yearbook Production vol. 44 (1990).

In 1994, as far as actual vs. recommended calcium intake is concerned, 63.9% of the Japanese population ingested less than the recommended daily dose, while approximately 40% received only 80% of the required dose. Nowadays, though, Japanese lifestyle is looking more and more European, including a change in dietary habits. This involves an increased intake of milk, milk products and animal proteins.

As can be seen in Figure 5, calcium content of water in Japan is lower than in Europe.

Fig. 5: Calcium concentration in commercial water.

HRT in Japan now

In 1992, the female population over age 45 represented 39.8% (25 million) of all (62 million) Japanese women; this percentage is estimated to be 47.2 (30 million) in 2000. In 1995, hormone replacement therapy for menopausal complaints has been prescribed to 1.2% of women aged 45-64, but this rate has lately been increasing. In the United States, the corresponding rate is approximately 35%, whereas in Europe it varies from just a few percentage points to over 40% (1995). Treatment is rather short-term, usually no longer than 6-9 months. The prevailing indication is, of course, menopausal symptoms, but many Japanese gynaecologists are well informed about the latest research on prevention of osteoporosis. The preferred regimen is monotherapy with estriol, or conjugated oestrogens combined with cyclical progestogen. The oestrogen patch has been introduced lately. In addition to HRT, Japanese doctors prefer prescribing vitamin D3, vitamin K, and calcitonin for inhibition of bone calcium absorption. Calcium supplementation is also considered important in order to recover bone loss and balance low calcium uptake from dietary sources. Furthermore, Japanese physicians favour prescribing antihyperlipaemic drugs such as HMG-CoA-reductase inhibitors and the like.

Despite the widespread knowledge about the benefits of HRT in preventing osteoporosis and reducing the incidence of CHD, stroke and Alzheimer’s disease, Japanese women do not fancy long-term HRT use because of concerns about an increased risk of breast cancer and endometrial cancer. In order to deal with these concerns, the Japanese Menopause Society – which has been developing quickly – and many other institutes have set up special menopause consulting hours. In our department these are called ‘Queen’s Corner’. It is expected that activities like this one will lead to an increase of HRT use in Japan.

References

1. Abridged life table [in Japanese]. Department of Health and Welfare (KOSEISHO). Tokyo; 1997.

2. Estimated future population [in Japanese]. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. Tokyo; 1997.

3. Hirota K, Honjo H, Shintani M. Factors affecting menopause. Adv Obstet Gynecol 1995;47:389-92.

4. Adlercreutz H, Honjo H, Higashi A, et al. Urinary excretion of lignans and isoflavonoid phytoestrogens in Japanese men and women consuming a traditional Japanese diet. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;54:1093-100.

5. Markiewicz L, Garey J, Adlercreutz H, Gurpide E. In vitro bioassays of non-steroidal phytoestrogens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1993;45:399-405.

6. Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA. Estrogen replacement therapy and coronary heart disease: a quantitative assessment of the epidemiologic evidence. Prev Med 1991;20:47-63.

7. Mary SA, Thomas BC, Claude LH Jr, et al. Soybean isoflavones improve cardiovascular risk factors without affecting the reproductive system of peripubertal rhesus monkeys. J Nutr 1996;126:43-50.