First Consensus Meeting on Menopause in the East Asian Region

Opening address

G. Benagiano

UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction,

World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

It gives me great pleasure to welcome all of you on behalf of the World Health Organization to this First Consensus Meeting on Menopause in the Far East Asia Region, organized by our Collaborating Centre here in Geneva.

We are very grateful to Professor Campana and his collaborators for all the efforts they have made to ensure the success of a meeting which is of great importance to us, as it deals with an issue of increasing concern for developing countries at a time when their populations are ageing considerably. Indeed, in 1990 there were an estimated 467 million women aged 50 years and over in the world. This number is expected to increase to 1200 million by the year 2030 [1].

Some 17 years ago, the World Health Organization convened its first scientific group meeting ever on the subject of the menopause to review existing information and to make recommendations for future research and clinical practice [2]. In response to the recommendations made in that report, attention has been given to population-based studies of the normal menopause, age at the menopause and the transition to the postmenopause. Symptoms of the menopause have been evaluated from the perspective of normal populations and not just from selected patient groups. The importance of contraception for women approaching the menopause (i.e. in the late premenopause) has been recognized by researchers, clinicians and governmental regulatory bodies. Numerous studies have been conducted on the benefits of hormone therapy in reducing the risks of cardiovascular disease and osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal women. This research has also necessitated continued study of the effects of hormone therapy on the risks of endometrial and breast cancers, although it has, so far, produced few conclusive answers.

Despite specific recommendations to address this issue, little is known about the menopause and its consequences in the developing world: almost all the research to date has been devoted to women in developed countries. The little cross-cultural research that has been done suggests that findings from developed countries about the menopause, its problems and their treatment, cannot be generalized to women living in other parts of the world. Even within developed countries, data on the risks and benefits of hormonal therapy are as yet inconclusive, and other therapies have received inadequate attention.

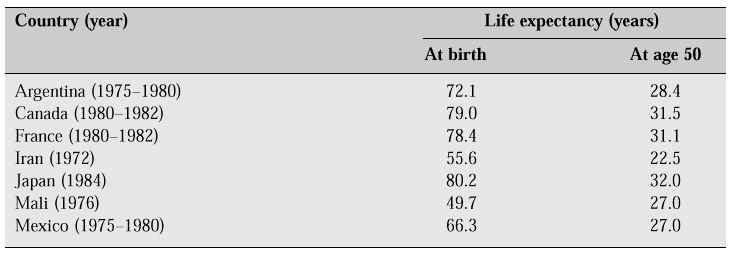

Fourteen years after the first meeting, a second scientific group meeting was organized in 1994 to address emerging issues and update our information on topics already covered in 1980 [3]. This update was especially needed, since — thanks to the major and remarkably similar increase in life expectancy observed almost everywhere in the world for women who reach the age of 50 years — many women nowadays spend a significant part of their lives in the postmenopausal period. Table I shows the life expectancy at birth and at the age of 50 for women in selected countries in different regions during the 1970s and 1980s.

Table I: Life expectancy at birth and at 50 years of age for females in selected countries in the 1970s and 1980s [4].

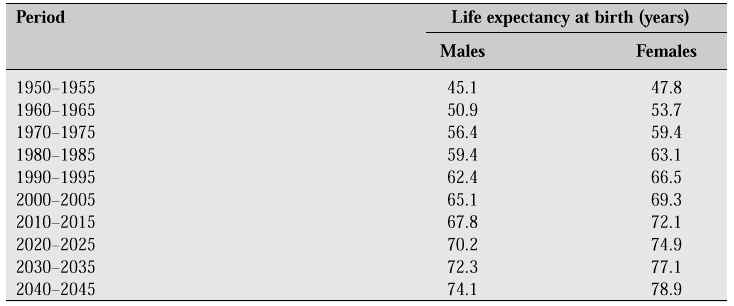

Table II: United Nations’ estimates and projections of life expectancy at birth in the world between 1950 and 2045 [1].

Once women have reached 50 years of age, life expectancy is between 27 and 32 years, except in Iran, where it is only 22.5 years. The data from Iran, however, are from 1972, the most recent year for which reliable data exist [4].

The United Nations estimates and projections of global life expectancy at birth between 1950 and 2045 are presented in Table II. Between 1950 and 1995, worldwide life expectancy for men increased by 17.3 years and for women by 18.7 years;

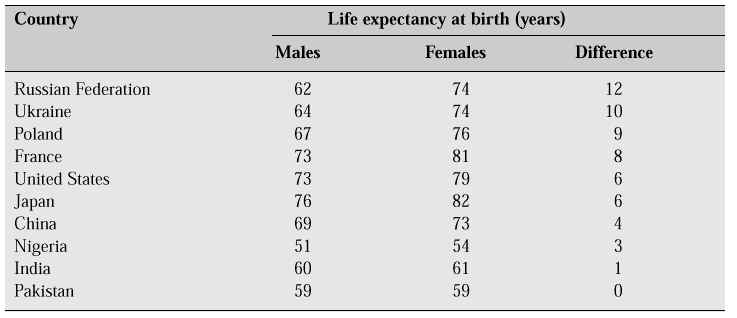

between 1995 and 2045, it is projected to increase by a further 11.7 years for men and 12.4 years for women. It can also be seen that between 1950 and 1995, the gender difference in life expectancy increased from 2.7 to 4.1 years and that by the year 2045, it is projected to be 4.8 years [1]. Indeed, already in 1992 this gender difference was about a decade in certain countries, whereas there was little, if any, difference in others (Table III) [5]

Table III: Gender difference in life expectancy at birth in 1992 in selected countries [5].

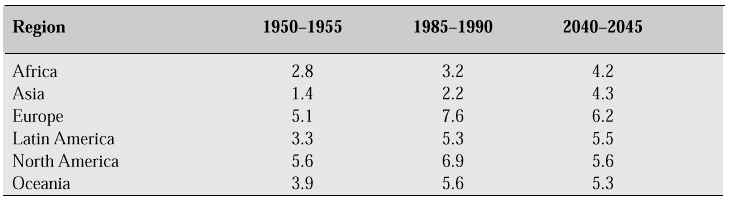

The data in Table III suggest that gender differences in life expectancy at birth may vary among the different geographic regions. That this is indeed the case is demonstrated by the data in Table IV. Although Europe is expected to retain its leading position in this respect during the first half of the 21st century, other regions will gradually catch up [1].

Gender inequality in life expectancy at birth is a global phenomenon, but what about life expectancy at 65 years? A comparison of data between 1950 and 1990 in selected countries is presented in Table V. It appears that during the 40-year period between 1950 and 1990, life expectancy at 65 years of age increased both for men and women, and that, at least in the countries shown in this table, the gender difference almost doubled [6]. Hence, it would appear that gender inequality in terms of life expectancy has been with us for quite some time, but it has only begun to cause concern during the last 15 years [7].

Table IV: Differences in life expectancy (years) at birth between women and men in 1950–1955 and 1985–1990, and projected differences for the period 2040–2045 [1].

The menopause is the time of a woman’s life when reproductive capacity ceases. The ovaries stop functioning and their production of steroid and peptide hormones falls. A variety of physiological changes takes place in the body: some are the result of the cessation of ovarian function, others are a consequence of the ageing process.

Many women experience the well-known symptoms that accompany the menopause. Most are self-limiting and certainly not life-threatening. Nonetheless, they are unpleasant and sometimes disabling. The problem for us today is that the prevalence of menopause-related symptoms among women in developing countries has not been properly evaluated.

More important than the immediate symptoms of the menopause are the effects of hormonal changes on many of the body’s organ systems. The most extensively studied effects are those on the cardiovascular and skeletal systems; they have been documented in developed societies, but little research has been carried out in developing countries.

To ameliorate the immediate and long-term consequences of the menopause, hormonal therapies have been recommended and are being used extensively in some societies. The therapies themselves have created new concerns about the increased

risk of neoplasia of the endometrium and possibly of the breast. Hormonal interventions raise complex issues where the health benefits achieved have to be contrasted with their cost for the developing countries, in both health and monetary terms. Therefore the task of identifying a research agenda in the field of the menopause for East Asia, where one-third of humanity lives, is a major one.

You have been called upon to advise the World Health Organization at the beginning of this process of evaluation of possible strategies to develop a research programme on the menopause which, for the first time, will focus on the needs of postmenopausal women of the developing world.

We know that these women are going to live considerably longer than their male partners. Our challenge is to ensure that the quality of their lives is such as to protect their dignity as well as their needs.

References

1. United Nations Department for Economic and Social Information and Policy Analysis, Population Division. World population prospects: the 1994 revision. Document ST/ESA/SER/A/145. New York: United Nations, 1995.

2. World Health Organization. Research on the menopause. WHO Tech Rep Ser 1981; 670.

3. World Health Organization. Research on the menopause in the 1990s. WHO Tech Rep Ser 1996; 866.

4. United Nations Department of International and Social Affairs. Demographic yearbook 1985. New York: United Nations, 1987.

5. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Information and Policy Analysis, Statistical Division. The world’s women, 1995: trends and statistics. Social statistics and indicators. Series K, no. 12. New York: United Nations, 1995.

6. World Health Organization. Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular diseases in elderly people. WHO Tech Rep Ser 1995; 853.

7. Diczfalusy E, Benagiano G. Women and the third and fourth age. Int J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 58: 177–88.